CV or Not CV, "How True?" is the Question

By *Annelize van Rensburg - www.signium.co.za

Qualifications fraud is a big problem in South Africa and, although not prominent at executive level, it does happen. To stamp out this practice, the National Qualifications Framework Amendment Act 12 of 2019 was signed into law on the 13th of August this year. It provides that people presenting false qualifications could serve up to five years in prison.

Being a businessperson who depends on honest, qualified staff, I am very happy about this development. In a country where corruption is exposed daily and where honesty and trust need to be reinstated, it will help prevent further fraud and corruption. At least there is now a material penalty to deter recruits from using forged qualifications.

However, the law does not solve the larger issue of candidates lying on their CVs.

In a struggling economy, jobseekers may be tempted to falsify information that could help them gain employment or skip some rungs on the ladder to the career and lifestyle to which they aspire. They might lie about previous titles held, their actual reward packages, their scope of responsibility, having a criminal record, being blacklisted or any other facts that either hinder or help their quest for their next top paying position.

Verification firm, Managed Integrity Evaluation, says that of 552,000 CVs it checked in 2017, 14.3% of candidates had misrepresented themselves or lied about their qualifications.

Executives typically face rigorous background checks and generally know better than to lie on their CVs. However, there are exceptions to the rule. For those who lack integrity, their desire to get ahead may tempt them to obtain false qualifications, withhold past wrongdoings or fabricate achievements.

Such actions are not only criminal but could bring into question the integrity of the hiring organisation's governance framework as well as having a negative impact on its growth and sustainability.

Yet, to cut costs, some companies are forgoing the extensive checks performed by executive search firms through their validation partners and the resulting analysis that gives assurance of a sound hire.

Executives are sometimes appointed by virtue of being a member of a trusted circle of business associates. Reward packages may be negotiated over a game of golf, and the position awarded without independent background checks. This is extremely risky.

Research has proved we’re not as good at reading people as we think. Knowing you can trust executive hires through fact-based research, trumps feelings of trust derived from regular social or business interactions. An appropriate rule of thumb is “better the devil you know” because that’s the devil you can avoid.In a time of public demand for better corporate governance, as well as transparency and justification of executive remuneration, every organisation must ensure the executives it employs have faultless track records. By using impartial executive recruiters or so-called headhunters, that engage trusted verification agencies to validate qualifications down to the finest detail, it will find the leaders it deserves.

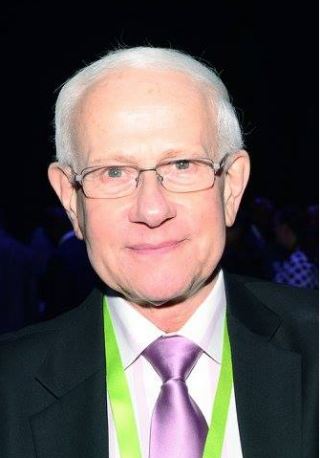

*Annelize van Rensburg is a director of Signium Africa (previously Talent Africa), a leading South Africa-based executive search and talent management company servicing sub-Saharan Africa.

What to do when integrity may get you fired?

What to do when … Integrity may get you fired

By Auguste Coetzer*, Director at Signium Africa (www.signium.co.za)

Rising levels of perceived corruption have sharpened the ethical challenge for those in responsible positions. When the spoils might run into billions, it seems you can be fired for doing the right thing and rewarded for doing what you know to be wrong. How do you stay on the side of the angels, stay in your job … and stay out of jail? The issue receives growing attention. The PwC study, Strategy & Recent CEO Success notes an international rise in ethical lapses and subsequent dismissals at senior level. It attributes the uptick to public outrage at corporate scandals, social media as a platform for experience-sharing and a 24/7 news cycle that makes any cover-up highly problematic.

The topic is also examined by author Ira Chaleef in his book, Intelligent Disobedience: Doing Right When What You’re Told to Do Is Wrong. Intelligent Disobedience indicates the impossibility of being only slightly dirty. You might object to an unethical practice and go along reluctantly, but your ethical lapse can still land you in jail. So, do you simply resign in protest and walk away? Sometimes, this is the only thing to do. You might then go public and become a whistle-blower – with huge personal consequences if you are labelled a ‘trouble-maker’. This is not always a wise move, and is often not necessary.

In a small market like South Africa, industry peers, professionals and specialists in executive recruitment are usually aware of the organisations where leadership is flawed and irregularities are apt to occur. Quitting an operation like this – or being fired for taking an ethical stand – holds no stigma. Your career will often resume an upward trajectory after an initial bump or two. In many cases, however, the issues are not nearly so clear cut. The organisation might decide on suspension rather than dismissal. You can then be pressured to go quietly. In South Africa, there have been cases where senior personnel have been suspended for years, leaving them and their careers in limbo. With this in mind, it may be advisable to avoid an outright rift in the event of unethical demands. Intelligent Disobedience suggests four techniques: Obvious shock. By your tone and facial expression indicate the request has taken you aback. Don’t give an outright refusal (yet). Your demeanour may be enough to prompt a rethink.

The boss or board may backtrack and subsequently abandon the idea without losing face. Seek clarification. Ask ‘Did I understand you correctly? Do you really want me to do this?’ You might even ask for the instruction to be put in writing. (For your own part, never sign any documents sanctioning unethical practices. This puts you in the cross-hairs while guilty parties stay camoflaged.) Suggest a better alternative. There may be a chance other, less dubious, steps could be taken and deliver a positive outcome. Emphasise self-preservation. Use expressions that enable a superior to retreat. Say, ‘This could make us look bad if this comes’ rather than ‘You will look bad.’ Point out that in the social media era, dirty secrets always come out eventually and this will not look good for ‘us’. But, at the end of the day, remember there are worse things than quitting a job or being fired from it … for instance, going to prison.

*Auguste Coetzer is a Director of Signium Africa (previously Talent Africa), a leading South African-based executive search and talent management company servicing sub-Saharan Africa.

The best defence against corporate failure...Individual Integrity

The best defence against corporate failure … Individual integrity By Auguste Coetzer* and J. Michael Judin**

Integrity has no expiry date. You’ve either got it or you haven’t. An honest, diligent company director does not become a crook on the make the moment some arbitrary term limit has been exceeded.

This states the obvious. However, current pressures in the realm of corporate governance and audit practice suggest now’s a good time to remind ourselves of basic principles in the conduct of business and the behaviour of directors. Inevitably, the implosion of the Steinhoff retail group and revelations about the role of Gupta-linked companies in state capture have raised questions about the ability of current regulation – specifically the King IV guidelines – to combat wrongdoing and sharp practice. The focus has fallen on the tenure of directors and audit firms. Long-term appointments supposedly contribute to cosy relationships and an ‘old boys’ club mentality’, allegedly compromising professional scepticism and rigorous scrutiny of corporate actions and accounts.

The supposed solution is frequent rotation of independent non-executive directors and audit firms. Pressure appears to be growing to get old faces out and new faces in. Momentum is such that it is almost certain mandatory audit firm rotation (MAFR) will be legislated locally while the definition of independence may be revisited, perhaps resulting in the automatic lapsing of independent status after nine years (on the British model). Currently, under section 92 of the Companies Act, audit partner rotation is mandatory in South Africa, not audit firm rotation, while King IV allows boards to exercise their judgment when an independent non-executive director appears to offend any of the criteria for independence, as long as a board can justify its view that independence of judgment and action is unimpaired. This may change as those calling for further legislation punt the merits of regular rotation. In effect, the proponents of rotation play up the benefits of a shake-up while playing down the value of experience. The danger is that institutional memory and industry knowledge will be sacrificed with no assurance new perspectives will improve company performance or corporate governance. Past errors might be repeated, incurring unnecessary costs while endangering competitive advantage and jobs.

Experience has traditionally been regarded as a key component of wisdom and a precondition for forward planning. Confucius tells us ‘By three methods we may learn wisdom: First, by reflection, which is noblest; Second, by imitation, which is easiest; and Third, by experience, which is the bitterest’. Of course, experience at the highest level – in the boardroom – is especially hard won. It should be noted that experience is still being gathered with MAFR. This state of flux has not impeded the global trend to mandatory rotation.

The EU has introduced MAFR, with a 10-year cap on client-auditor tenure. Brazil has a five-year cap, as does China (for banks and SOEs) while the UK prefers a 10-year limit. Yet a growing body of research suggests presumed benefits cannot be substantiated and the risks of auditing failure are higher in the early years of a relationship; undercutting arguments about complacency setting in over time. The efficacy of rotation as a defence against fraud is also open to question. MAFR was in place in Italy years before the Parmalat scandal, but was no defence against frauds so massive they rocked the country. Sometimes doubt sets in after prolonged trial. For example, Spain embraced the concept for several years, then dropped it. Research continues and real-life experience is still being gathered. However, arguments in favour of a wait-and-see approach appear to have lost ground to growing agitation for regular rotation of audit firms and independent directors. The challenge for proponents and sceptics alike is how to make the best of these changes when they come.

Clearly, the known risks should be addressed; for instance, the danger that rotation will deplete industry knowledge and institutional memory. One suggestion here is that a phasing-in period be introduced. The established audit firm (or established directors) could remain on board while replacements learn the ropes and draw on the experience of their immediate predecessors. With corporate change on the near-term horizon, it is also appropriate to focus on challenges specific to South Africa; such as the need to strengthen boardroom diversity. Here, the phasing-in principle might be extended to include a mentorship period for newly appointed young directors. While welcoming a new generation of directors, it makes sense to confront a generational issue – low levels of digital literacy on ageing boards of directors. A McKinsey Quarterly article of 2016 noted that “only 116 directors on the boards of the Global 300 are digital directors”. Furthermore, two McKinsey surveys report that only 17% of directors say their boards are sponsoring digital initiatives while only 16% say they fully understand how industry dynamics are changing in the face of digital attack. Yet one in three directors believe digital disruptors will overturn their business models in the next five years.

In response, some US firms are setting up technology committees while hiring chief digital officers and appointing digital directors. South African companies face similar challenges, though board composition may not yet reflect their willingness to cross the digital divide. The geek with the knowledge and insight to save a traditional organisation from digital disaster is probably under-30 with a ring in his (or her) nose, and you don’t see many directors answering to that description in South African boardrooms. In all these rotational, mentorship, diversity and digital scenarios, we should acknowledge that a key issue is talent availability. South Africa’s skills pool is limited. The number of experienced, proven and respected individuals with sound directorial credentials is finite. We can legislate change, but we then have to find the people to make the changes work. Clearly, integrity and intellectual honesty are non-negotiable. They are the critical requirements of all contributors to company performance, whether newcomers to the boardroom or old hands A shake-up that weakens corporate governance must be avoided at all costs. Ethical leaders with strong values are the best guarantee that change is a change for the better.

*Auguste Coetzer is a Director of Signium Africa (previously Talent Africa), a leading South African-based executive search and talent management company servicing sub-Saharan Africa. www.signium.co.za

**J. Michael Judin is a partner in the Johannesburg law firm of Judin Combrinck Inc. www.elawnet.co.za Though he writes here in his personal capacity, he is on the King Committee, was part the task team that wrote King IV™ and chaired the subcommittee on the chapter dealing with negotiation, mediation and arbitration as contained in King III. He is a non-executive director of, and legal adviser to, the American Chamber of Commerce in South Africa and co-chairman of the Corporate Governance International Development Subcommittee of the American Bar Association’s business law section.