The conservation paradox of rhino trophy hunting

Written by: Miquette Caalsen Save to Instapaper

Johannesburg – On the 25th of February 2022, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries, and the Environment (DFFE) announced the hunting quotas for the hunting of, among other species, 10 black rhinos in South Africa. The announcement was met with immediate shock and scorn, as many decried the hunting of the critically endangered black rhino.

SA largest exporter of trophies

Critics of the rhino trophy hunt quota brought up the Humane Society International/Africa’s (HSI/Africa) Trophy hunting by the numbers report numbers to show that South Africa is the largest exporter of trophies of wildlife species in the world. While the numbers in the report may be accurate, it does not differentiate between rhino in national parks and rhinos in private ownership. This is an important distinction as the number of rhino (black and white) in private ownership is increasing, while the rhino population in national parks are decreasing.

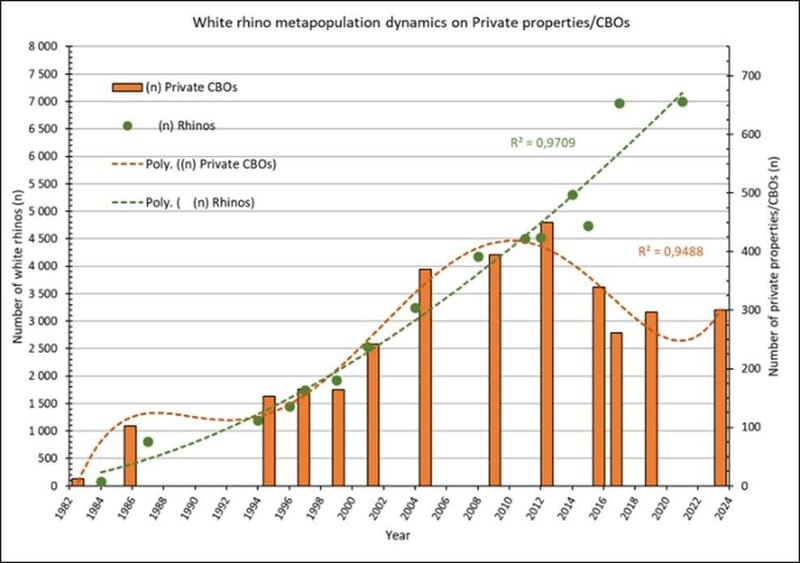

The current estimate of the white rhino population as of 2020 in the Kruger National Park (KNP) stands at a shocking 2,607 animals – an alarming decrease of nearly 75% in the last decade. The South African population was estimated at 17,208 in 2015 and between 17,212 and 18,915 in 2021, with an all-time high of 20,43 in 2012. The privately owned population was estimated at 4,735 (28% of the national population) in 2015, and between 6,218 and 6,968 in 2017 (Furstenburg et al 2022, in preparation).

Two issues that do not belong together are often conflated into one crisis, that is, the legal hunting of rhino and the insatiable poaching complex running rampant in South Africa’s national parks that has in recent years started affecting private reserves as well. The distinction is a crucial one to understand the real challenges facing rhino conservation in South Africa.

Legal hunting vs. illegal poaching

Poachers appear to hunt at a regular rate, suggesting a stable market, primarily in Eastern countries, for the export of rhino horn, inter alia, falsely believed to have medicinal properties. This rate of poaching is far above the sustainable growth rate of the rhino population. In contrast, the comparatively lesser affected private ranches have been able to maintain an average annual growth of 14,4% from 1984 to 2021, significantly greater than the natural biologic growth rate of around 6%, and the IUCN/CITEC target of 5%.

Figure 1: Annual rhino metapopulation dynamics on private properties/CBOs across SA (Furstenburg et al 2022, in preparation, data Balfour [2020, 2018], Balfour et al. [2015], Goodman et al. [2018])

The distinction between illegal poaching and legal hunting is exacerbated when it is taken into account that poachers will kill any animal they can track down, whereas legal hunts (especially on private reserves) are determined according to the age, gender, and health of the individual animal. When poachers kill a young cow, they remove not only one, but as many as 10 rhinos from the population-continuum as one rhino cow can have up to ten calves during her productive years. Legal hunts on private reserves preserve the growth potential of their herd by selecting the animals that are no longer a net positive to the herd – problem animals, unhealthy animals, or “excess” animals.

It may be difficult to understand the idea of an “excess animal” in a species that is listed as critically endangered. An excess animal is identified once the population of rhino on a limited area reaches its peak, meaning there are the maximum number of animals that the land on which they live can sustain. Unlike elephants who continue growing in population to problematic numbers – a phenomenon currently wreaking havoc on the biodiversity in the KNP – rhino will increase its population in a particular area until it reaches its social carrying capacity. The social carrying capacity is the maximum population density before conflict start arising between rhino bulls and even bulls and calves. This means that over time a rhino population stabilises at a specific number for a given area. In terms of a well-protected wildlife sanctuary, where the key aim is biodiversity, this would be the ideal density.

But herein lies the problem, there is currently no government managed sanctuary or reserve that is safe from the unnatural predations fuelled by the poaching complex. The skewing of herd numbers means the population growth of the species is negatively affected, leading to a downward trend in population growth on top of the loss of individual rhinos to poaching. Private game ranchers attempt to maintain the natural growth rate of rhino by selectively hunting individual animals to continually stimulate the growth rate in situations where population stability is slowing the growth rate – or where poaching has affected the growth rate negatively.

Hunting as a necessary tool

This is where the legal hunting quotas become a necessary tool in the continual conservation efforts of rhino in South Africa. The quota is based on an estimation of the overall population. This allows conservationists to target individual animals for a hunt that will, with its removal from the herd, produce a net positive on the overall health and growth potential of the herd. Since 2013 to 2021 an average of 0,4% of the national rhino population are being hunted as an incentive for the private growth rate of 14,4% (Furstenburg et al 2022, in preparation). This model has been particularly successful on game ranches, where the income from legal trophy hunts can afford much greater security measures to protect the herd from poachers.

The argument is often made that in the case of excess animals the animals should be moved to an area where the rhino population has become extinct. Whereas this solution seems like a viable solution, multiple questions arise as to who will stand in for the massive costs involved in resettling a large animal as well as who will take responsibility for the security of the animal in this re-populated area? If the initial extinction of the rhino in the area was due to illegal poaching, it stands to reason that the herd was insufficiently protected and that any new population resettled under the same conditions, would only be led to slaughter as the initial cycle of poaching will merely repeat itself.

Ultimate responsibility

The conservation and preservation of a species is a complex, multivariate problem that requires close cooperation between all responsible bodies, government, regulatory, conservation and private game rancher. Unfortunately, there is currently no clear communication across all these bodies to fully grasp the enormity of the problem. Population numbers are out of date, and without a clear picture of the impact of all hunting activity, both legal and poaching, decisions are made based on broad assumptions. This not only speaks to the issue of hunting quotas for legal hunts, but the rules governing the existence of private game ranches.

Currently, it is estimated that 65% of white rhino in South Africa are on private land and should these be shut down based on emotive politics, the future of the rhino is almost certainly, total extinction. With the lack of current numbers reported for national parks it is impossible to know the total number of rhino (black and white) in South Africa, and where these herds are concentrated. There is also a lack of clear distinction between legal hunts and illegal poaching, as the numbers of exported trophies do not and cannot correlate to the number of hunts. The general obfuscation of wildlife and hunting numbers adds to the overall misconceptions about wildlife adding to the contentious relationship between animal rights and welfare groups and the wildlife ranching community.

Now, the future existence of the rhino population in South Africa appears to lie in the hands of the increasingly besieged private game ranchers. These ranchers are becoming victims of their own success as the increasing numbers of rhino in private hands are leading to a surplus of animals. However, they are subjected to over-regulation of the trade in rhino products, which is steadily causing a nett loss for ranchers as the cost of maintaining a healthy herd of rhino are not recouped through sustainable trade. To protect 20 white rhinos on a private game ranch comes to R60,000 per month for which no income can be generated though any form of sustainable use.

The politics of conservation under the intense pressure of highly emotive special interest groups is not the place to make rational, scientifically backed decisions on the future preservation of the rhino population. In a world where the human expansion into previously wild areas is accelerating, all conservation of endangered species will lie in the hands of those with the means and will to protect them for future generations – both public and private. To this end, difficult and sometimes unpopular decisions need to be made by those with the experience on the ground of the reality faced by wildlife conservationists and ranchers. In the end, one will not survive without the other, and it is on that paradigm that the future of our endangered species rests.

Miquette Caalsen

Get new press articles by email

The Pulse Latest Articles

- Education Is The Frontline Of Inequality, Business Must Show Up (December 11, 2025)

- When The Purple Profile Pictures Fade, The Real Work Begins (December 11, 2025)

- Dear Santa, Please Skip The Socks This Year (December 10, 2025)

- Brandtech+ Has 100 Global Creative Roles For South African Talent (December 9, 2025)

- The Woman Behind Bertie: Michelle’s Journey To Cape Town’s Beloved Mobile Café (December 9, 2025)