Dr Nthabiseng Moleko is an Economist at Stellenbosch Business School

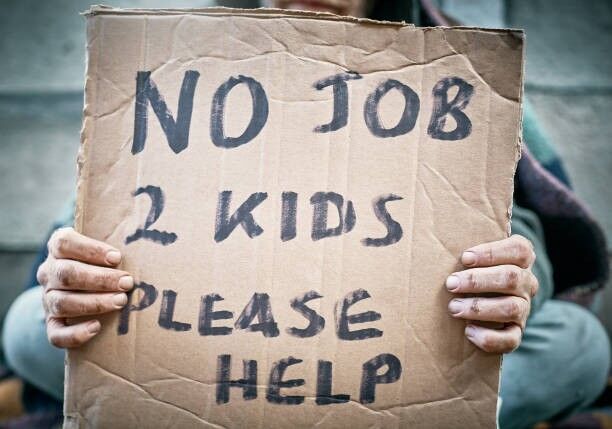

The 2023 quarter 3 Labour Force Survey paints a grim reality. The unemployment crisis is not a recent development. It has been persisting for at least the past decade.

Unemployment according to Stats SA a decade ago (quarter 3 of 2013) was at 4.9 million people with the majority (3.2 million) of the unemployed experiencing long-term unemployment.

Today unemployment is at 7.8 million, meaning 31.9% of South Africans are unemployed. This figure is still giving us an optimistic view of unemployment as it excludes those who have sadly given up looking for work. The number of discouraged workers adds an astounding 3.2 million people to the unemployed, putting the true rate of unemployment to an astonishing 41%.

It’s disheartening for me to note that nothing is being done about it. Despite the size, scale and prolonged length of the unemployment crisis, woefully our economic and labour market policies remain unchanged. Perhaps, it is more apt to say we have surpassed the crisis levels. Yet, the trade, monetary, industrial and agricultural policies remain invariably the same. And we as South Africans wonder in dismay at the worsening unemployment trends. A re-evaluation of policies to enhance labour absorptive capacity are urgently needed. Policies that are not working cannot remain untouchable.

The size of discouraged work seekers, which is but a proportion of the total unemployed is generally not included in the narrow definition that is cited largely by media and government. Discouraged work seekers alone are currently equal to the number of the long-term unemployed in 2013 at 3.2 million. Youth in rural areas, and townships who were unemployed a decade ago, have remained unemployed. In addition, new entrants in the labour market annually add an average contribution of 290 000 to the unemployed, totaling to an increase 2.9 million unemployed in the past decade. That by any labour market policy standards and economic output measurement is a crisis.

It has recently been reported that the narrow unemployment rate – which excludes the 3.2 million discouraged work seekers – has declined by 0.7% this quarter. We must move towards a more comprehensive reporting of the unemployed (non-economically active), so the true extent of the problem becomes apparent to the everyday South African.

The full picture highlights the following: 7 out of 9 provinces have unemployment levels exceeding 42%, Gauteng is at the door at 39.4% with the expanded definition. Rural regions are unfortunately economic wastelands. These regions are unable to offer their population in the majority, the youth, with opportunities at scale – to afford them the ability to not only contribute to the South African growth story, but the opportunity to fulfill their destiny. An unemployment level of 51.2% in the Northwest means from Rustenburg, Brits, Phokeng to Marikana and Mafikeng most of the labour force are doing nothing. Cities, towns and villages are filled with a despondent, crushed, discouraged population who are at the peak of their energy, strength and mental vigour. The same for Mpumalanga, Limpopo, Free State, Eastern Cape, Kwa-Zulu Natal and Northern Cape.

A national unemployment rate of 41.2% is beyond a crisis. Significantly more effort needs to be implemented to ensure our youth escape a life of alcohol and substance abuse, mental health issues, transactional relationships and even crime, to simply put food on the table.

The interventions needed must increase the absorption rate of youth between 15-24 years old, which sits at 11.2% in this quarter. It is significantly lower than 59.6% of the 45-54 year olds. Our economic growth even at its highest levels post-democracy showed concerning trends of jobless growth. Chronic unemployment lies within our youth whose unemployment levels are almost double the national levels at of 60%. Yet all the economic plans, strategies and reports have no impact on the absorption rate or even the participation rate directly measured.

No economic plan and strategy should be supported by South Africans that doesn’t refer to impact on unemployment levels of youth, black African women, and rural areas who have in the history of the labour force survey displayed unemployment levels higher than the national average. If women and youth are employed, unemployment levels would decline as the labour absorption rate would improve.

The plans we are implementing are yielding no fruit. Imagine laying a seed under the earth and it yields no fruit despite your watering, tilling and inserting fertilisers in the ground? A tree that bears no fruit must be cut down. Likewise economic policies that have not improved labour absorption rates which decrease unemployment rates and impede chronic unemployment levels must be cut down.

Get new press articles by email

Latest from

- To Arrest a Student Is to Arrest the Future

- The Crumbling Foundations of South Africa’s Steel Industry - A Wake-Up Call for Reform

- Upscale Christmas Lunch with a Local Twist

- Leveraging Artificial Intelligence to Leapfrog African Industrialisation

- Unseen Struggles Chronic Illness and Disability in the Workplace

- SUNDAZE SUMMER EVENTS AT DURBANVILLE HILLS

- Stigma - The Leading Cause of Untreated Mental Health

- Workplace Support Critical After Breast Cancer Diagnosis

- Make Your Home Feel Like a Top Hotel with These Spring Cleaning Tips

- Cataracts Leading Cause of Preventable Blindness

- Work Can Be Both Good and Bad for Mental Health

- Breast Cancer on the Rise in Younger South African Women

- How to give longevity to your leftovers

- Five reasons why “moral regeneration” failed in South Africa

- Durbanville Hills Official Wine Partner To Masterchef South Africa

The Pulse Latest Articles

- Celebrating 125 Years Of Hansgrohe: Setting The Beat Of Water Since 1901 (February 25, 2026)

- Celebrate Pokémon Day At Toys R Us Menlyn On 28 Feb (February 25, 2026)

- The Great Generational Handover: Why South Africa’s Middle Managers Are The Hinge Of 2026 (February 23, 2026)

- Jennifer Hadley Photography Announces A Curated 2026 Katmai Bear Photography Season (February 18, 2026)

- Life Doesn’t Have To Be A Lot – The In-between Drink (February 17, 2026)